If you’re like me, when you think about fossils in the eastern USA, you probably think of either Cenozoic fossils along the eastern and gulf coasts (e.g. Miocene/Pliocene/Pleistocene shark teeth, whale vertebra, and shells in Virginia and the Carolinas) or Paleozoic fossils further inland (e.g. Cambrian trilobites in Georgia or Carboniferous plants in Pennsylvania).

Or, if you live in the Piedmont and Blue Ridge areas of the Appalachian mountains like we did until last year, you don’t think about fossils at all, because all you have are igneous and metamorphic rocks!

Less well-known, however, is that the eastern USA has good Mesozoic (the “age of dinosaurs”) deposits, including Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous fossils. The first reasonably complete dinosaur discovered anywhere in the world was the Cretaceous Hadrosaurus foulkii, found in New Jersey in 1858. While not as extensive as the Cretaceous exposures in the east, the eastern USA has a series of long Triassic and lower Jurassic basins running roughly parallel with the coast. One of the best fossil sites in these basins is the Solite Quarry.

Note: The Solite Quarry is privately owned and not open to the public. It is an active quarry, and both dangerous and illegal to trespass on the property. We excavate at the Solite Quarry as volunteers with the Virginia Museum of Natural History.

Located near the border of North Carolina and Virginia, the Solite Quarry is composed of layers of shale, mudstone, and sandstone that may represent an upper Triassic, shallow, rift valley lake. The Solite is known as a Konservat-Lagerstätte, a German paleontological term roughly translated “conservation storage place” (I prefer to think of it “preservation mother lode!”). A Konservat-Lagerstätte is a place where fossils are preserved extraordinarily well, and Solite is famous for the details visible on Triassic insects. These insects are found in a narrow bed only a few centimeters thick. Just above this insect layer is a second thin bed that preserves the remains of plants, fish, reptiles, and “clam shrimp” (formerly, “conchostracans,” which they’re still often called).

Looking down the rock that has already been excavated toward the insect and fish beds still being removed.

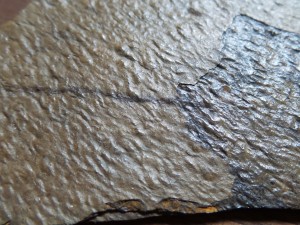

A mass burial layer of clam shrimp, tiny crustaceans with a protective shell. Each dimple represents an individual.

While the insects are usually too small to see, plenty of visible fossils are found in the “fish bed” above. Plant parts and seeds are found on occasion (I found a Fraxinopsis, shown here) but the real star of the Solite is the amazingly preserved fish and reptiles. The most common reptile here is the presumably aquatic Tanytrachelos ahynis (illustration of a swimming one here) a smaller relative of the better-known long-necked Tanystropheus (learn about the latter here and here). Tanytrachelos was an archosauromorph reptile. This means that it was related to the archosaurs, a group of reptiles which includes crocodilians, pterosaurs, and dinosaurs. In life, however, they probably looked something like a cross between a lizard and a salamander. While dinosaurs tend to get all the attention, there are certainly many other fascinating reptiles that lived during the Mesozoic!

My wife Christa was able to come excavate on my June and September trips. Here she’s just uncovered a Tanytrachelos and a fish.

Hundreds of Tanytrachelos specimens have been found at the Solite, but they are rare elsewhere. On this trip, we uncovered seven specimens. They are usually fairly flattened, but otherwise well preserved.

Here’s another view of the same specimen. The tail is going toward the top of the picture, and the hind legs splay out to each side. The torso (ribs and spine) goes through the middle of the picture. The head and arms, if they are all there, are obscured by part of the rock and what is probably a piece of fossil plant.

Christa’s fish. We didn’t know the species, but a variety of fishes, including members of the coelacanths, have been found here.

While I enjoy collecting fossils for myself, that’s not our purpose at the Solite, and we do not keep these specimens. They are scientifically important, and are placed in the Virginia Museum of Natural History for research and preservation.

The Solite Quarry is part of the Carnian Triassic Cow Branch Formation. Although no dinosaur body fossils have been found in the Solite, dinosaurs and pterosaurs have been found in formations of similar depth, and ichnofossils (trace fossils) indicate that dinosaurs walked here.

This slab, perhaps once an ancient muddy shoreline, preserves around a dozen dinosaur footprints walking in different directions. Standing behind it are Ray (in the gray shirt), the VMNH lab technician, and Alex (in the white shirt), a geologist.

Close-up of a tridactyl dinosaur track. Some Triassic tracks can’t be matched to known species, so there is a reasonable chance that if a dinosaur fossil were ever found here, it could be a new species.

Next time, I’ll talk more about the experience collecting and other species found here.

To be continued…

Matthew Speights

Latest posts by Matthew Speights (see all)

- Solite Quarry, Part 1 - March 24, 2016

- I’m collecting in the rain… - March 15, 2016